Read the Full Series

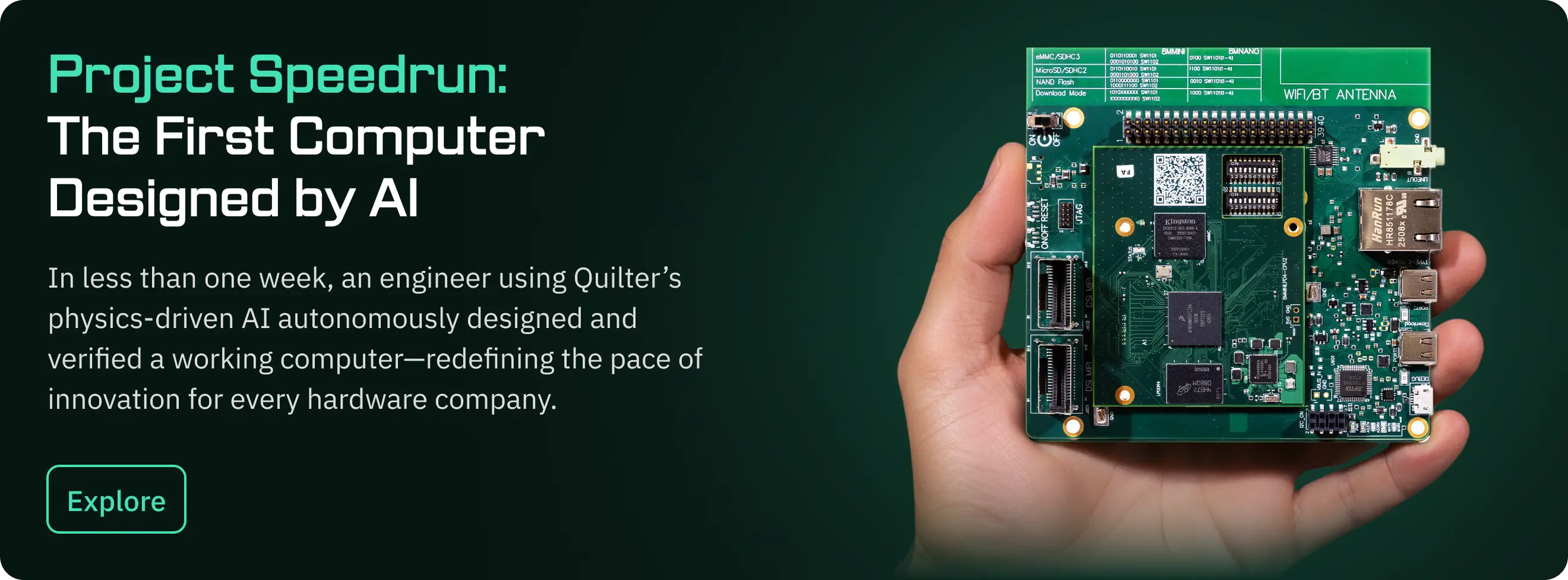

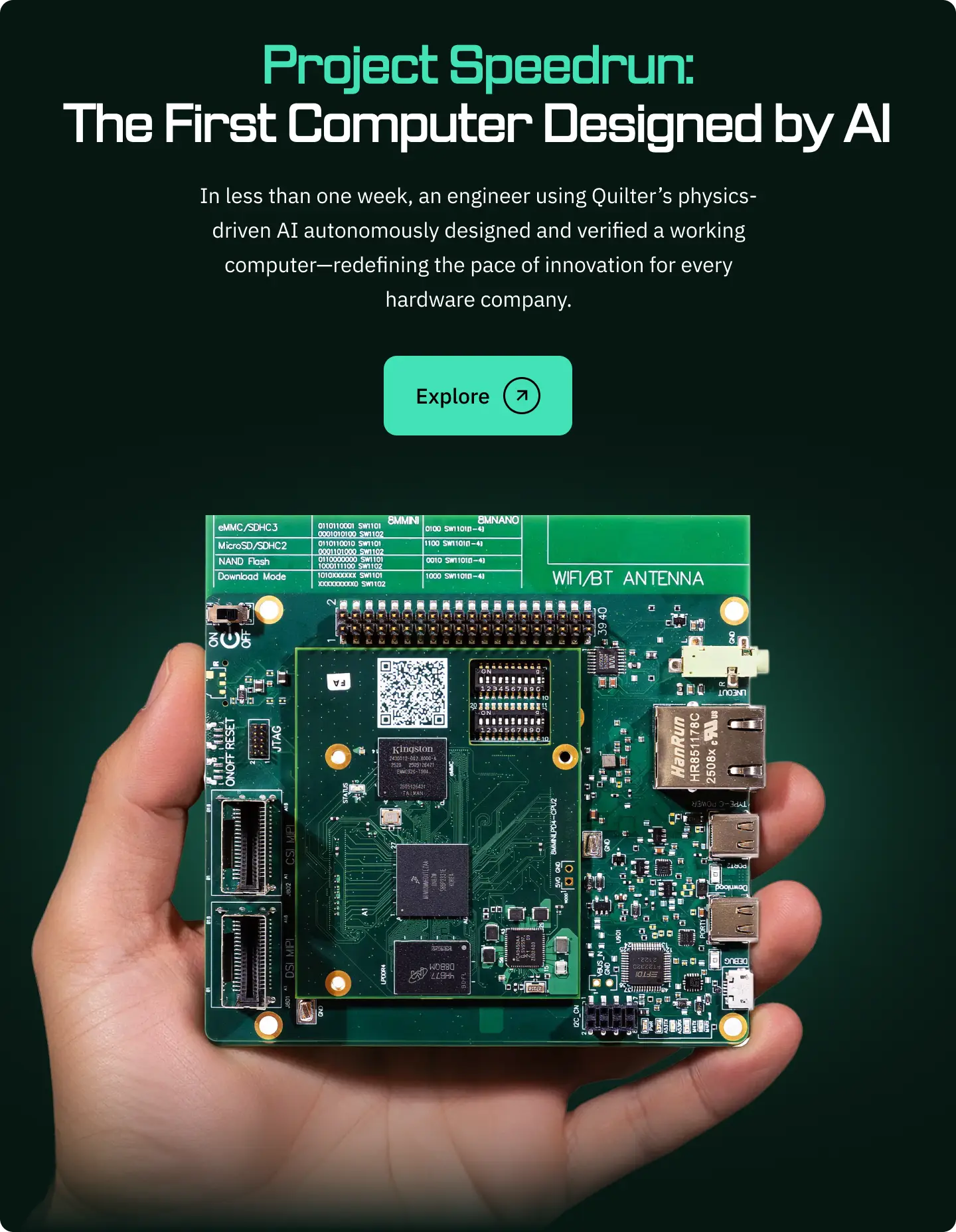

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

Engineering as Engagement

Stephen Newberry describes his daily work in a way that initially sounds almost unserious. He says engineering feels like playing video games all day. The remark is easy to dismiss until you listen to the context in which he offers it.

“I really feel like I get to play video games all day,” he explains. “I get to play around with simulation tools, analyze how things work, draw geometry, experiment with layout, and see how the results change.”

What he is describing is not leisure. It is immersion. It is the sustained attention that comes from working inside a system well enough to explore it freely. Signal integrity, in his framing, is not a checklist or a static body of rules. It is an environment you learn how to navigate.

“I really feel like I get to play video games all day. I get to analyze how things work and see how the results change.”

That posture toward engineering shapes everything that follows. Newberry’s authority does not come from dramatic intervention or loud conviction. It comes from time spent noticing.

A Nonlinear Path into Signal Integrity

Newberry’s ability to see systems clearly is inseparable from the path that brought him there. His route into electrical engineering was not direct. After a brief and unsatisfying start in college, he enlisted in the Coast Guard. There, he worked as an electrician, often on lighthouses and shipboard systems where failures were not abstract possibilities but immediate operational problems.

The experience changed how he understood electricity. He learned through hands-on diagnosis, practical repair, and responsibility for real infrastructure. He also learned that formal theory often arrives later, once the need for it becomes obvious.

That foundation stayed with him when he returned to school years later. At Rutgers, he completed his degree quickly and moved into a small defense contractor with deep Bell Labs lineage. The environment demanded flexibility. He wrote embedded code, developed FPGA logic, designed PCBs, and participated in long design reviews where senior engineers dissected problems aloud.

Those reviews became an education of their own. Newberry learned by listening. He learned how experienced engineers framed questions, which details they lingered on, and how rarely conclusions came before understanding.

Discovering Signal Integrity by Doing It

When Newberry first encountered the phrase signal integrity, he had already been solving SI problems for months. He was managing schematics and coordinating layouts when the term began circulating around him. Rather than glossing over it, he stopped to investigate.

“I remember the word kept popping up, signal integrity, and I had no idea what it meant,” he recalls. “So I borrowed a copy of Howard Johnson’s book and went through it.”

What he found resonated immediately. Thin traces. Tight geometries. Energy moving through materials with very little tolerance for ambiguity. The appeal was not academic elegance. It was the challenge.

“This idea that we’ve got super thin traces on small circuit boards and we’ve got to get the data from point A to point B and it’s got to work,” he says. “It’s a wonderful challenge.”

“We’ve got super thin traces on small circuit boards and we’ve got to get the data from point A to point B and it’s got to work.”

That emphasis on outcome remains central to his thinking. Signal integrity matters because systems must function under constraint. Beauty follows behavior, not the other way around.

How Intuition Actually Forms

As Newberry’s career progressed, something subtle began to change. He started noticing problems before simulations confirmed them. Vias felt wrong. Return paths looked compromised. Margins seemed tighter than the numbers suggested.

He does not describe this as instinct or talent. He describes it as exposure.

“Intuition comes from experience,” he says. “It comes from having seen something before and recognizing the pattern.”

Logic still matters. Procedure still matters. What changes over time is the speed at which relevant details surface. Early in his career, those details were invisible. Today, many of them appear immediately.

“When I first started, there were a lot of things that would not have jumped out at me,” he explains. “Now I can look at a design and see via stubs, anti-pad issues, or transmission line details that weren’t accounted for.”

That ability does not guarantee failure or success. Many boards work with imperfections. What it offers is awareness. It narrows the space of surprise.

Learning the Hard Way Where Attention Belongs

One of Newberry’s most formative lessons came from a mistake he still remembers clearly. Focused on high-speed interfaces, he assumed a low-speed connection was safe to ignore. The logic felt sound. The frequencies were low. The risk seemed minimal.

The board failed anyway.

“I focused so much on the high-speed interfaces that I completely ignored some slow-speed signals,” he says. “Sure enough, we had SI failures on the low-speed side because I didn’t account for certain parasitics.”

A respin followed. So did a permanent change in how he allocates attention.

“I focused so much on the high-speed stuff that I ignored the slow-speed interface, and that’s where the failure was.”

The lesson was not about speed. It was about assumption. Signal integrity problems do not announce themselves where you expect them. They appear where models feel least necessary.

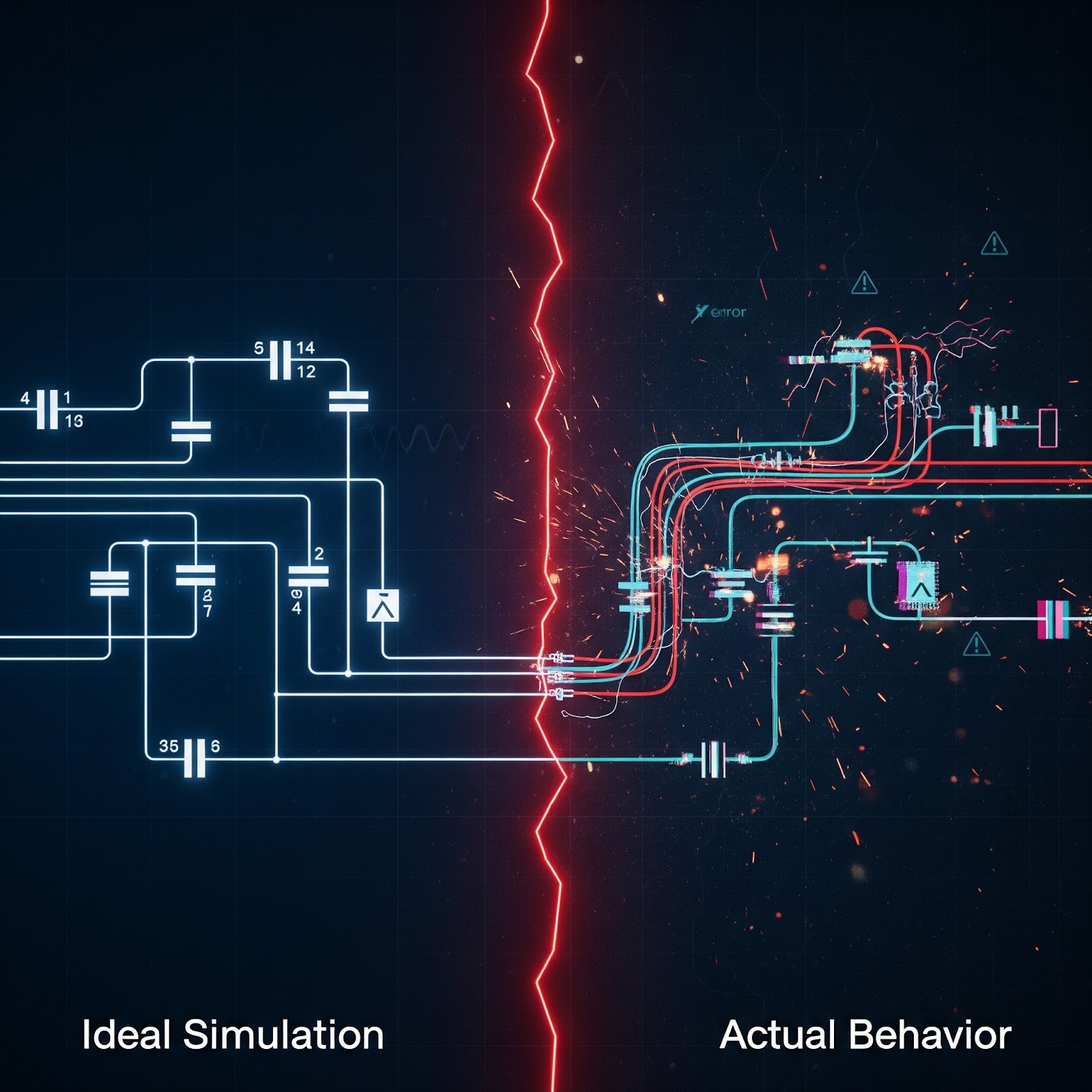

Trusting Simulation Without Surrendering Judgment

Newberry remains deeply invested in simulation and analysis. He does not treat tools skeptically out of distrust. He treats them carefully out of respect.

One phrase recurs often in SI circles, and Newberry repeats it without irony. Everyone believes their own simulation. Nobody believes anyone else’s. The saying persists because it describes behavior accurately.

Simulation produces clean plots. Converged results create confidence. Without grounding in measurement and benchmarking, that confidence can drift away from reality.

“There’s a trap in blindly trusting simulation tools,” he says. “Benchmarking against measurements and understanding where you can trust a tool really matters.”

That stance does not diminish simulation. It contextualizes it. A solver becomes useful when its assumptions are understood and its outputs are interpreted, not accepted automatically.

Leadership as Attention, Not Authority

Throughout his career, Newberry has avoided defining himself through hierarchy or debate. He does not gravitate toward public arguments about standards or ideology. Instead, he pays attention to how understanding moves through organizations.

There are far more board designers than signal integrity specialists. Complexity increases faster than headcount. Bottlenecks form when expertise stays centralized.

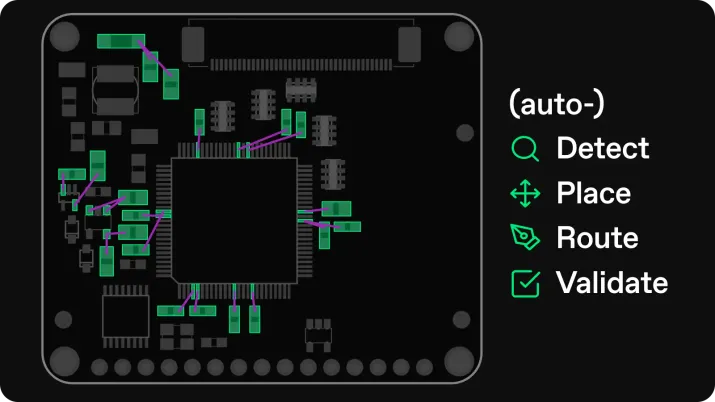

His solution is not replacement but distribution. Intelligent automation. Constraint-aware guidance. Design aids that inform layout decisions earlier rather than escalating problems later.

“The more information we can get to board designers earlier, the better,” he says. “That makes everyone more effective.”

That perspective reflects a view of leadership grounded in enablement. Expertise scales best when it is shared deliberately.

The Habit That Matters Most

When asked what future engineers should focus on learning, Newberry does not point first to a tool or a theory. He points to a habit.

“The biggest thing is learning how to learn,” he says. “The best engineers I’ve met have this innate curiosity and desire to explore.”

He describes tinkering at home, experimenting with systems outside his formal role, and letting adjacent knowledge seep back into his professional work. Engineering, in his view, remains a lifelong process of translation and curiosity.

That mindset explains his opening metaphor better than any credential list could. Playing the game means staying engaged long enough to notice the patterns. It means remaining open to correction. It means understanding that the board reveals itself slowly, and only to those who keep looking.

Design Reviews as Knowledge Infrastructure

Newberry often credits design reviews as the most formative part of his early career. Not the presentations, but the listening. Long sessions where experienced engineers reasoned through systems aloud taught him how expertise actually moves.

“In those reviews, I learned so much just by listening,” he says. “The things people pointed out, the way they discussed issues, it stuck with me.”

Design reviews serve as institutional memory. They capture hard-earned lessons before they become folklore. They also surface assumptions while there is still time to challenge them.

The loss of rigorous review culture creates subtle erosion. Teams become efficient at executing known patterns and fragile when confronting new constraints. Over time, organizations forget why certain rules exist and which exceptions are dangerous.

For Newberry, reviews are not bureaucratic hurdles. They are learning environments where intuition transfers through exposure.

Good Enough Depends on Where You Are Standing

Engineering regularly operates under the banner of good enough. The phrase hides a tremendous amount of nuance. Newberry treats it carefully.

“Good enough is such a variable benchmark,” he observes. “It depends on the industry and the application.”

In aerospace or defense systems, tolerance for ambiguity approaches zero. In consumer electronics, tradeoffs are often acceptable if user impact remains limited. The same electrical behavior can be catastrophic in one context and irrelevant in another.

Problems arise when good enough becomes detached from context. When rules are applied uniformly without revisiting assumptions, systems stagnate. Engineers begin to defend precedent rather than outcomes.

Newberry has little patience for dogma. A design either meets its requirements or it does not. Aesthetic preference, historical convention, or internet wisdom cannot substitute for evidence.

AI, Automation, and the Shape of Judgment

Newberry’s perspective on AI-driven design tools is shaped by direct experience rather than speculation. During his graduate work, he explored neural networks trained to approximate electromagnetic solver outputs. The results were promising but imperfect. That imperfection mattered.

“Even my work was really more of a toy compared to real tools,” he admits. “But it showed what might be possible.”

Approximation accelerates exploration. It enables iteration. It does not absolve engineers of interpretation. AI tools generate candidates. Humans decide which candidates matter.

That division of labor shapes Newberry’s optimism. Automation should move understanding upstream, not eliminate it. Constraint-aware guidance helps layout designers avoid known pitfalls. It reduces unnecessary escalations. It does not replace judgment.

“There are more board designers than SI engineers,” he says. “The more information we can give designers earlier, the better it is for everyone.”

“Automation should make engineers more effective, not remove responsibility.”

That framing avoids extremes. Tools that obscure their assumptions create new failure modes. Tools that surface reasoning invite collaboration.

Advanced Packaging and the End of Casual Assumption

Newberry’s work in advanced packaging reflects many of these themes. Early assumptions about packaging as simple interconnection fall apart under modern constraints. Chiplet architectures compress distances while multiplying interfaces. Margins shrink. Crosstalk increases. Behavior becomes sensitive to geometry in unfamiliar ways.

“Before I got into it, I thought packaging was simple,” he admits. “I was wrong.”

Advanced packaging demands explicit reasoning. Decisions that once lived safely on monolithic dies now interact through layered structures with complex electromagnetic behavior. Optimization becomes continuous rather than episodic.

In that environment, intuition still matters. It guides attention. It highlights risk. It never replaces verification.

Restraint as a Leadership Signal

One of the most striking aspects of Newberry’s approach is restraint. He does not rush to claim certainty. He rarely frames problems as battles to be won. His confidence appears in where he slows down.

Experienced engineers often develop the ability to sense when something feels off before articulating why. Newberry recognizes that feeling and treats it as a cue to investigate rather than a license to assert.

“Sometimes you just know something doesn’t quite fit,” he says. “Then you have to reason through it.”

Leadership emerges through that behavior. Teams learn when to pause. They learn that questions matter more than answers delivered too quickly. Over time, that culture reduces surprise and improves trust.

Seeing What Others Miss

Signal integrity, in Newberry’s telling, is not about dominance or mastery. It is about perception. It is about developing the patience to notice small details and the humility to verify them.

Boards do not fail because engineers lack intelligence. They fail because assumptions go unexamined. Experience teaches where to look first.

Over time, the board begins to speak. Traces reveal intent. Vias suggest compromise. Margins hint at stress. Engineers who listen carefully gain time. Those who rush lose it.

Stephen Newberry’s discipline rests in that listening. He trusts tools enough to use them deeply and doubts them enough to check. He treats intuition as earned. He leads through attention.

In a field increasingly crowded with automation and abstraction, that posture matters more than ever.