Read the Full Series

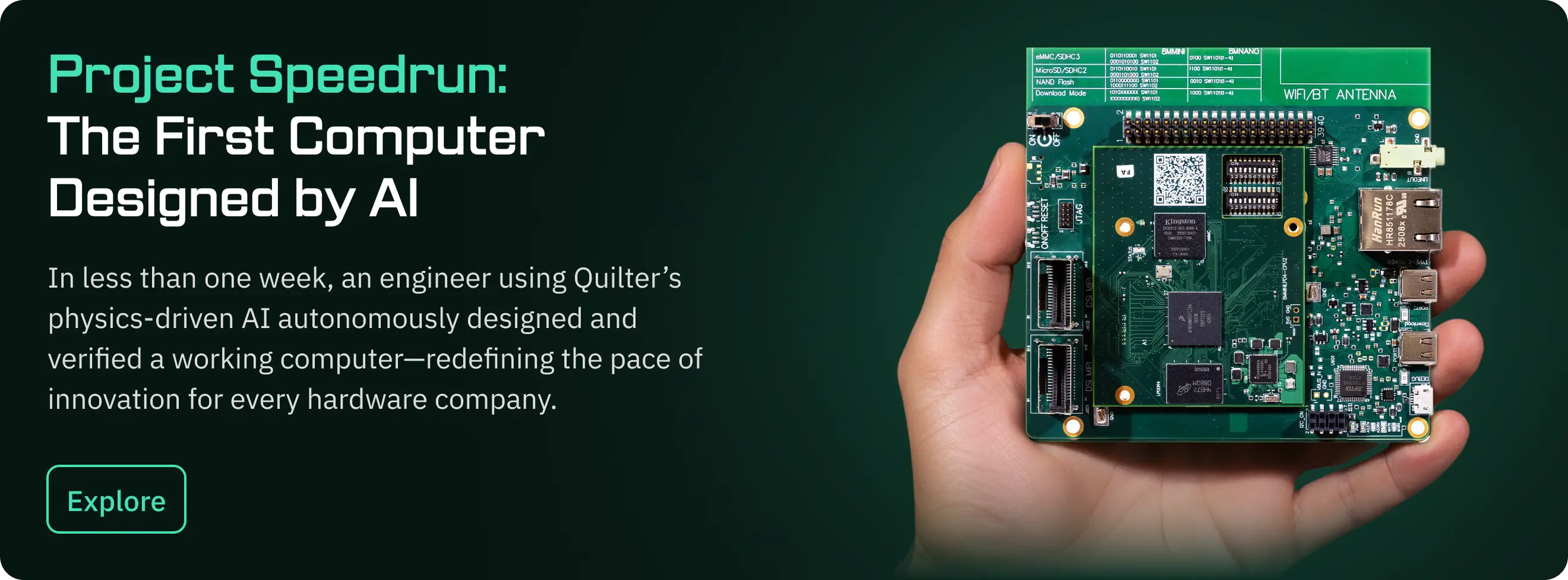

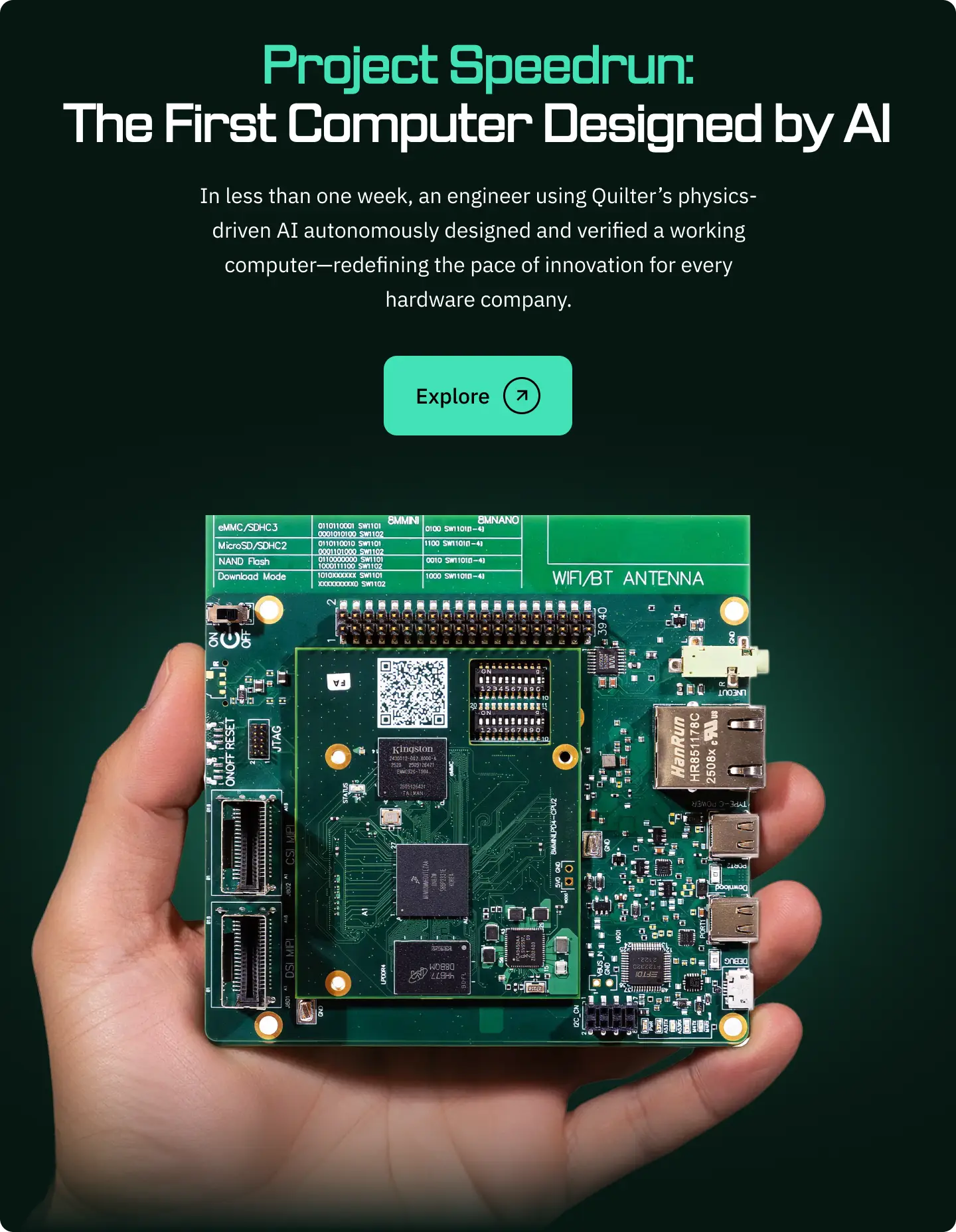

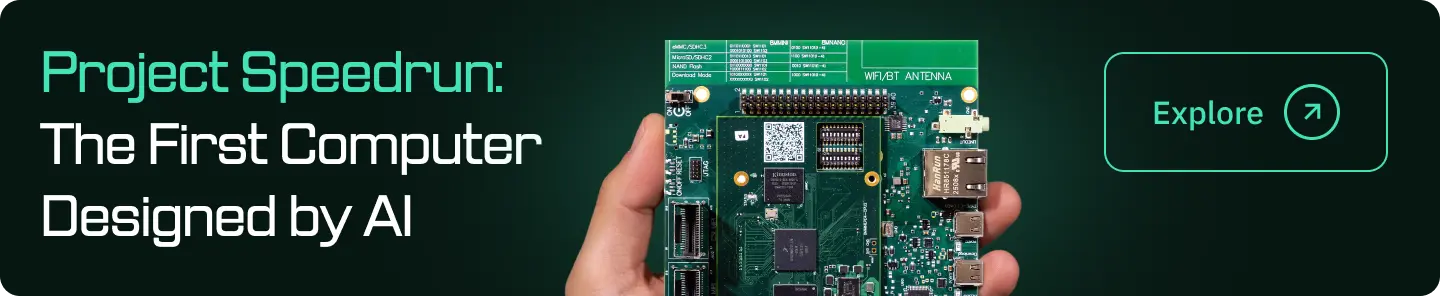

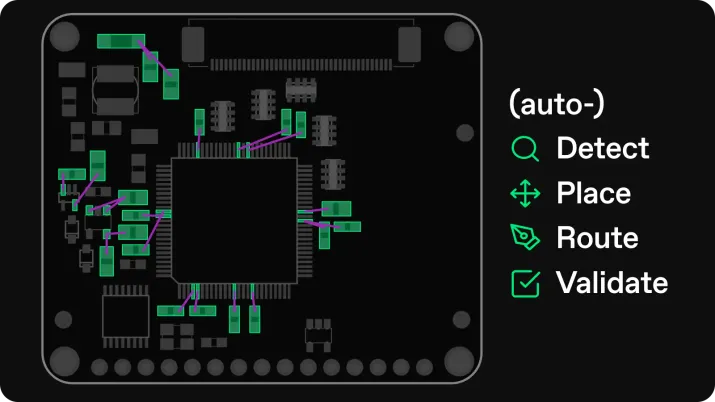

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

For Boris Clémençon, engineering has always been about decoding the invisible — the equations, the data, the geometry behind how things move and behave. With a background in mechanical engineering and a PhD in computational optimization, Boris has navigated the worlds of aerodynamics, data science, and satellite systems.

His journey from Dassault Aviation to Amazon’s Project Kuiper now brings him to the frontier of AI-driven electronics. In every domain, he’s followed the same principle: “There’s so much we don’t know, and so little we can’t learn.”

Origins

“I have always been a big nerd,” Boris laughs. “Playing with astronomy books and all things that my family could bring me.” Long before he had a computer of his own, he recalls, “I was, I guess, 18” already programming on his TI-89 calculator. Curiosity was the constant variable. His studies in mechanical engineering quickly turned mathematical, drawn toward partial differential equations, meshing, and optimization, the invisible scaffolding of how things are shaped, simulated, and improved.

That fascination for structure and form became a lifelong theme: from his postdoc in Cambridge on shape optimization to his later work decoding encrypted flight data, Boris built a career from understanding how complex systems hide their meaning in code.

Journeys in Engineering

After his PhD, Boris joined Dassault Aviation, working on shape optimization for military aircraft. “I was working on the Rafale jets,” he recalls, “and some of the components were actually from the 90s.” One day, he stumbled on what he calls his “Rosetta stone” moment. “There’s this cartridge — it looks like a Nintendo 64 cartridge — with weird encoding of the data. Everyone thought most of it was lost. I went to the library, found an old paper document with decoding rules, and managed to reconstruct all the flight data from the last ten years.”

That dataset included confidential insights but it also marked a turning point. The thrill of discovery, the power of mathematics, and the human curiosity to connect dots others overlook became Boris’s tools for every problem since. From CFD solvers written in Fortran and C to machine learning pipelines at Amazon, he’s kept one eye on the physics, one on the data, and both on the story they tell together.

Why Quilter

“I wanted to go back to startups,” Boris says. “It was killing me a little bit before, but I said, okay, I want to try again and I don’t want to screw it up.” After seven years at Amazon, he was ready for an environment that valued invention over inertia. “Working for Kuiper, everything around me was electronic. I said, that sounds very interesting — and I’ve got a lot of skills to do that, so why not?”

At Quilter, Boris brings a fusion of computational geometry, data analysis, and cloud-scale machine learning to hardware. His path mirrors Quilter’s ethos: bridging software and electronics, curiosity and execution, physics and AI. “You always invert a matrix,” he jokes, “no matter the field.” But beneath the humor lies the truth that systems thinking transcends domains.

Beyond the Workbench

When he’s not debugging or deriving, Boris builds with his hands. “I do love woodworking,” he says. “I built my own workshop downstairs with all the basic tools, hand tools, and power tools. I use it to fix my house, which needs a lot of love and attention.”

During the pandemic, necessity became craftsmanship: “Everything was so expensive, I had to do it myself: masonry, electricity, plumbing, construction.” He also spent years in martial arts, twelve years of judo and a stint with Brazilian jiu-jitsu before a car accident made him trade the mat for the workshop. It’s a familiar story: resilience, iteration, precision just in a different medium.

A Line to Remember

“There’s so much we don’t know, and so little we can’t learn.” It’s a sentence he once told his sister, but it doubles as a thesis for his career — and for the kind of minds shaping Quilter’s culture.

Closing Note

Boris embodies the bridge between old-world engineering rigor and new-world data fluency. His story reminds us that curiosity is a universal language — one that translates from Fortran to Python, from aircraft to algorithms, from craft to code.