Read the Full Series

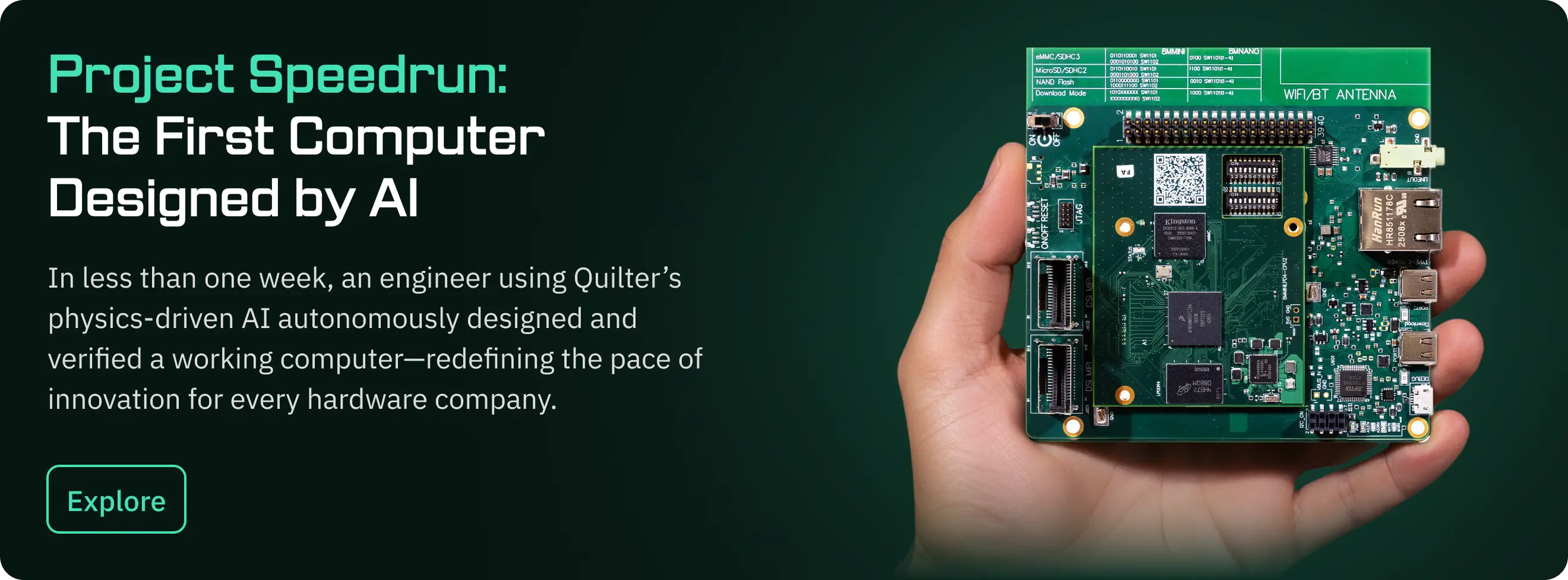

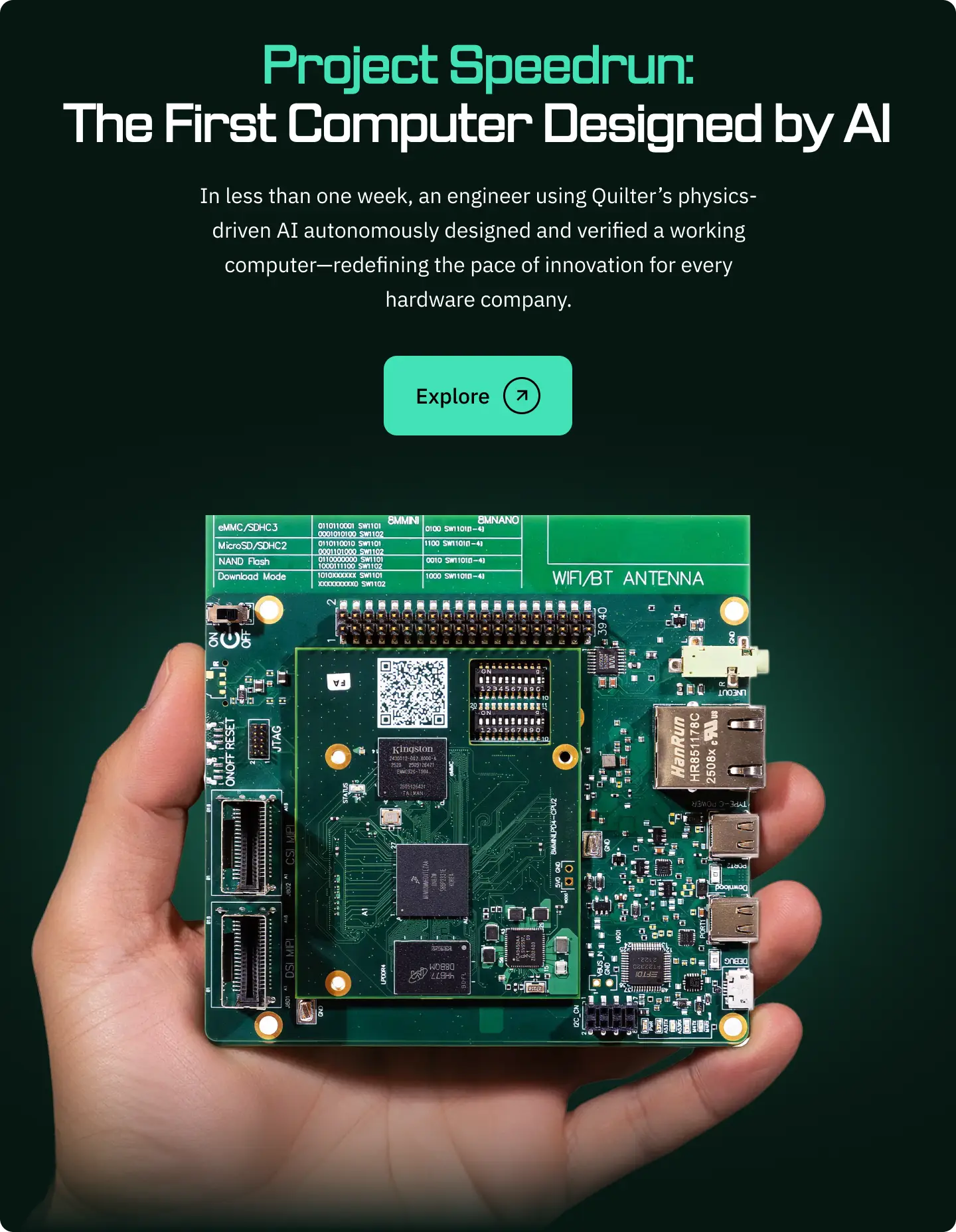

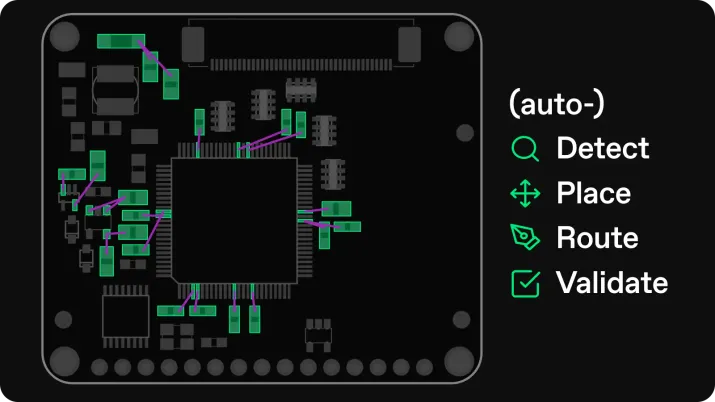

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

What Actually Limits Hardware Progress

Hardware programs rarely fail because engineers are unable to solve technical problems. Over time, physics yields to persistence, experimentation, and iteration. What resists resolution far longer is coordination across people, teams, and incentives.

Pooya Tadayon spent nearly three decades working across semiconductor test, packaging, and long-horizon pathfinding. Reflecting on that experience, he described the imbalance directly:

“I always said technology is easy. At the end of the day, the stuff that we're doing, I don't mean to trivialize it, but technology, at the end of the day, it's not that hard.”

That observation does not deny complexity. It reframes where difficulty accumulates over time. For Pooya, the persistent challenge was not equations, materials, or tools. It was navigating disagreement, ego, and alignment among highly capable people.

“The issue or the challenge for me was always the people, right?”

Where Progress Actually Slows Down

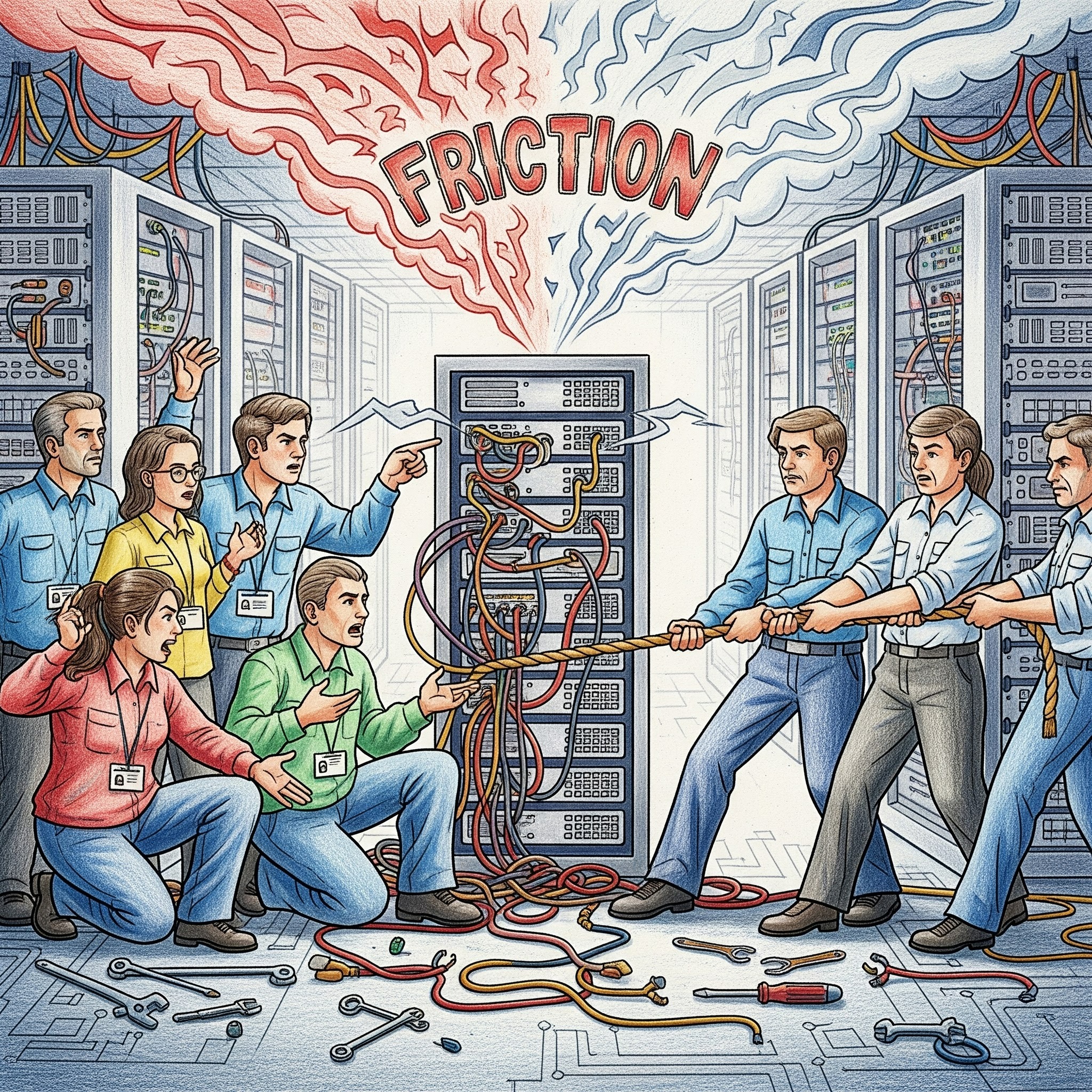

Smart Teams and Structural Friction

Modern hardware development requires coordination across electrical, mechanical, materials, manufacturing, and test disciplines. No product reaches market without multiple cross-functional interactions. Despite this interdependence, organizations often assume collaboration will happen naturally.

In practice, friction increases as teams become more technically proficient.

“When you get a lot of smart people in a room, you get a lot of big egos that you have to deal with. Everybody wants to do it their way.”

These conflicts do not arise from lack of capability. Each discipline brings valid expertise and legitimate risk awareness. The difficulty lies in maintaining focus on shared outcomes rather than individual conviction.

“Managing through that and trying to get everybody focused on the end goal and to just work on the issue and, you know, trying to cut through the personalities and the different ways that people work and all that, that to me is consistently been the toughest part in terms of making progress in the industry.”

While hardware consistently wants to persevere through technical difficulties, to explore challenges from schematic through simulation, often times it can be the ability to navigate a conversation that proves the greater challenge than the navigation of a maze of chips and traces.

Simulation as a Necessary Shift

From Empirical Purism to Practical Modeling

Early in his career, Pooya relied heavily on empirical data. Physical measurement carried more weight than analytical output.

“When I started out way back when, I was not a big believer in these simulation and modeling tools. My take was I don't really care what the simulation modeling says. It's empirical data that matters.”

That stance changed as systems grew more complex.

“Things started to get more complex… it was just becoming incredibly difficult and time consuming to go get empirical data on every different permutation. It just wasn't practical, otherwise we'd never get anything out the door.”

Simulation became necessary to guide exploration and narrow effort.

“I actually became a strong advocate for simulation and modeling, whether it be electrical simulation or mechanical modeling, or thermal modeling, etc. To help guide… the direction of where things are going.”

Yet Pooya remained explicit about the limits of modeling. The takeaway more that technology is here to aid us. Software, tests, are all available to improve our ability to produce and output more miracles, rather than have us be entirely reliant on them.

The Limits of Modeled Confidence

Assumptions as the Hidden Risk

Simulation accelerates work by allowing teams to explore sensitivity without building hardware for every scenario. It does not eliminate the need for skepticism.

“If your input parameters aren't good or if you're, if the boundary conditions you input into the simulation, especially if you're doing a mechanical or thermal simulation, if you don't have the correct boundary conditions or the boundary conditions are not a reflection of reality, then the results you get are bogus.”

Errors often surface late, after decisions feel settled.

“I've also seen so many cases where the modeling and simulation tools just spit out bogus results.”

These failures rarely come from solver defects. They arise from human inputs and unchecked assumptions.

“Don't just believe everything that it spits out. You have to trust but verify.”

This is a continued message I’ve seen across a number of our Hardware Rich Development interviews: nothing built by humans is perfect, and everything in physics is an interpretation of what we think is possible. Simulation results should always be fact-checked with real, physical examination: what is the device actually doing and telling you?

Pathfinding and Emotional Discipline

Operating in Persistent Uncertainty

Later in his career, Pooya led pathfinding teams working on problems five or more years ahead of deployment. Uncertainty was constant.

“When you're working on things that had never been done before, you're basically… dealing with what's perceived as a showstopper effectively. Every week.”

Progress followed a predictable cycle.

“Every week we would solve one problem, but we would uncover another problem.”

Sustaining momentum required emotional discipline.

“Try to keep emotions out of it and keep an even keel.”

Overreaction drained energy without improving outcomes.

“Don't get too excited when you have a success one day and don't get too depressed if you find a problem the following day.”

The beauty of working on the bleeding-edge, the discovery frontier, is that nearly every experiment and effort turns into a surprise, and every surprise is an opportunity to learn either what to do more of in the future, or to learn what to not to do next time.

Specification, Compromise, and Tradeoffs

Understanding Where Requirements Come From

Product specifications often appear authoritative but reflect ambition as much as feasibility. Pooya approached them with seriousness and realism.

“When a product spec comes out, I look at it and, you know, I take it seriously. But at the same time, I realize that, you know, these are ambitious targets and there's going to be compromises along the way.”

The critical step was understanding their origin.

“Where do these numbers come from? … I want to distinguish between challenging the numbers versus understanding where they came from. … Once you understand where they're coming from and what the basis is behind them, you kind of get an understanding of, well, which ones are more important or which ones are higher priority than others.”

This understanding enabled prioritization, a bane of near every hardware team leader when faced with different KPIs from different stakeholders: market time, product iteration, research, lifecycle management, and more are all leading to unique interpretations of the same root product.

Time as the Dominant Constraint

Optimization Versus Market Reality

Perfect solutions lose value if they arrive too late.

“You can spend 10 years trying to optimize something and get the exact product with the spec out, but you missed the market completely.”

For Pooya, delivery outweighed perfection.

“That's like the most important metric. Get product out the market.”

Validation Failures That Reach Customers

When Process Discipline Breaks Down

One of the most painful lessons involved a failure that escaped into customer shipments.

“Everybody thought this is very low risk. It's a low risk process. We've been doing this for 20 plus years.”

The assumption proved false.

“Some of the equipment had a part in there that was rubbing against another part and creating metal shavings. … We weren't doing another test. We were just shipping to the customer and the customer was identifying these shorts. … That stuff just drives people nuts. … You learn from that and you don't make that mistake ever, ever, ever again.”

The experience left a lasting mark. However, important as a representation that: you, yes reader, you too can make a mistake, even a massive mistake, and maintain your job, learn from it, learn to tell others about this years and decades later.

So often in our work I think fear of making mistakes enables sluggish innovation: if you risk failure then that means you risk being perceived negatively, so why risk failure at all? But I think in many cases the risk must be worth the reward, to push ourselves into bolder and bolder territories.

Education, Problem Solving, and Capability

What Actually Matters Over Time

Advanced mathematics played a smaller role in daily work than many expect.

“The number of times that I've used calculus or differential equations in my work is exactly zero. … Go study what you're good at, but work on developing your problem solving skills.”

Adaptability mattered most of all. Time and again these hardware leaders, in their varying capacities of technical leadership, are demonstrating that critical thinking skills and problem solving skills tend to be more important and necessary for a strong team member than any aptitude toward math or exact memories of formulas.

Final Synthesis: What Actually Limits Hardware Progress

Across packaging, testing, simulation, and leadership, Pooya Tadayon’s experience converges on a single reality. Technical problems yield to rigor, iteration, and discipline. Organizational problems persist unless confronted directly.

Simulation, modeling, and advanced tools accelerate exploration. They do not resolve ambiguity on their own. Specifications articulate ambition. They do not remove tradeoffs. Processes capture intent. They do not guarantee discipline.

What ultimately governs hardware outcomes is judgment exercised under pressure. Teams must decide when to trust models and when to verify reality. Leaders must determine when consensus substitutes for analysis and when analysis substitutes for alignment.

“Technology is a solvable problem.”

Progress depends on whether organizations treat people, process, and verification with the same rigor they apply to physics.

Hardware does not fail because equations break down. It fails when judgment is deferred, assumptions go unexamined, and responsibility becomes diffused.

That is where the real work begins.