Read the Full Series

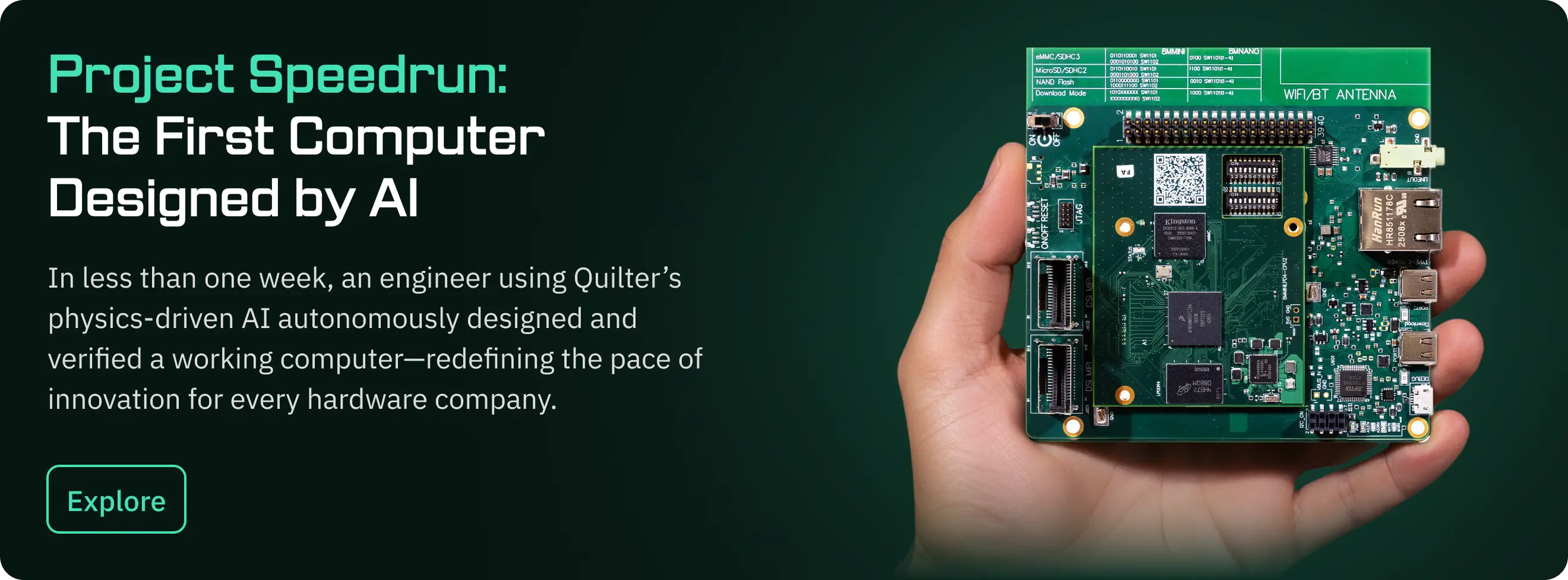

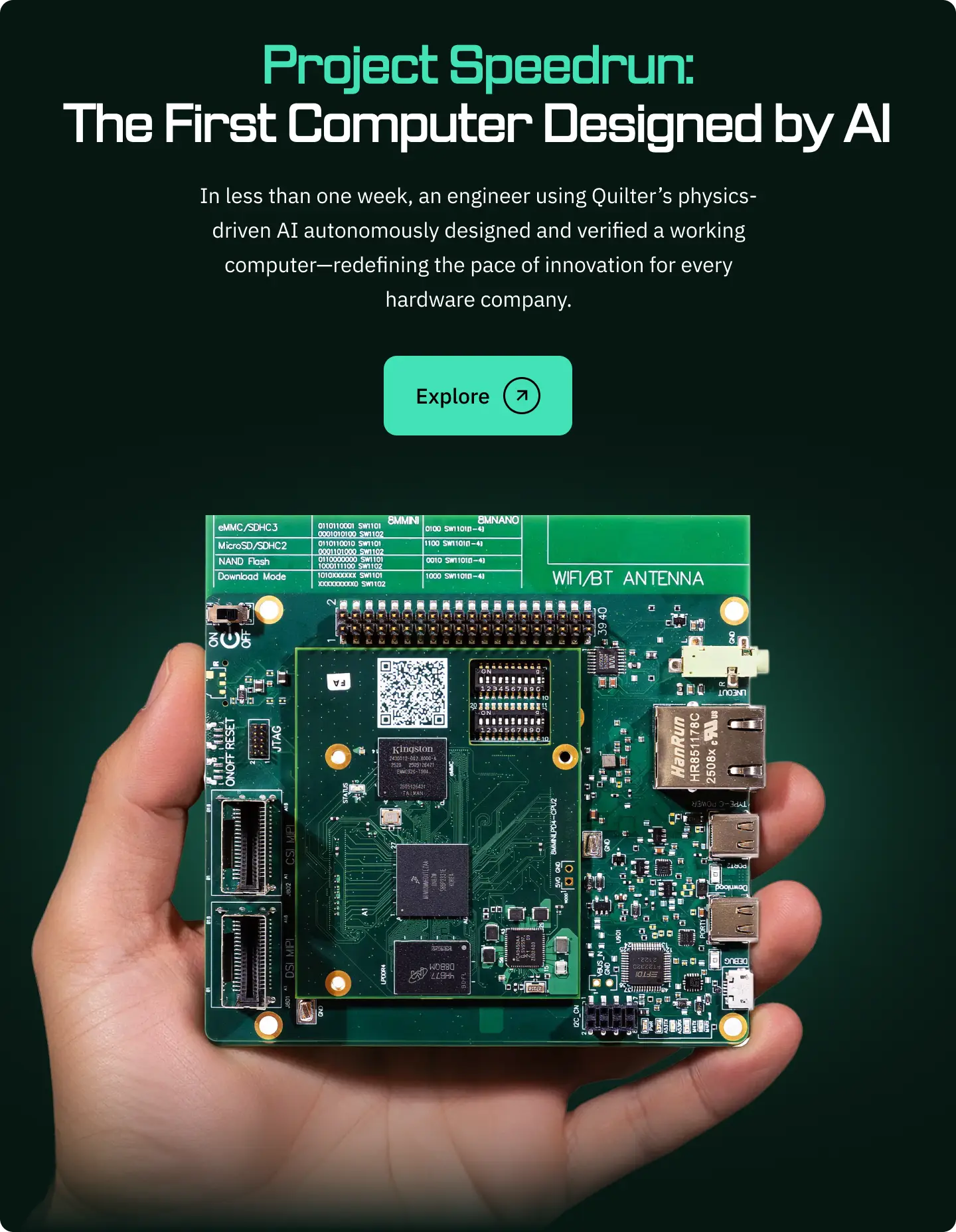

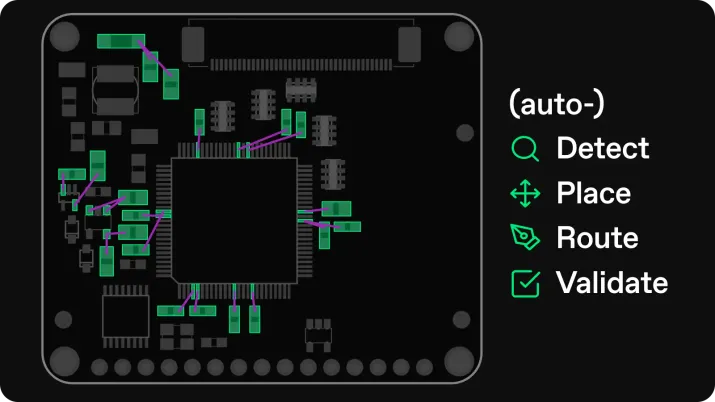

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

Humans in the Loop — Quilter

At Quilter, progress rarely announces itself loudly. It shows up as momentum that feels uninterrupted: meetings that happen when they should, teams that stay focused, crises that never quite become disasters. Stephanie Ngo lives inside that invisible layer. As an executive business partner at Quilter, she operates less like support staff and more like structural reinforcement—quietly absorbing complexity so the rest of the company can move faster.

Stephanie’s path to Quilter did not follow a traditional tech trajectory. Her career began in the entertainment industry, where she spent nearly eight years at an artist management startup, eventually working as both an executive assistant and artist manager. “We managed a roster of artists, with a core focus on rap, alongside musicians spanning multiple genres,” she explains, describing an environment where coordination, trust, and discretion mattered as much as talent. “I was exposed to a lot of… managing the teams like operations, learning how to provide a really white glove experience for folks internally and externally.”

That early exposure to fast-moving, high-pressure ecosystems would become the throughline of her career—even as she moved into tech, fintech, autonomous vehicles, and ultimately, deep-tech hardware software at Quilter.

Origins: Learning How Systems Really Work

Stephanie’s formative professional years were not about tooling or process diagrams; they were about people under pressure. In entertainment, there is no margin for disorganization. Artists move quickly, schedules shift without warning, and reputations hinge on reliability. “You don’t really have life outside of work,” she notes candidly of that period, describing a culture where after-hours still meant working hours.

After feeling she had “hit [her] peak” in that industry, Stephanie made a deliberate decision to grow. She transitioned into tech in the Bay Area, first at Lyft as a recruiting coordinator supporting executive teams, then as an executive assistant. When her manager moved to Plaid, Stephanie followed, supporting business operations and finance. Later, at Cruise, she found herself embedded with engineering and hardware teams spanning both domestic and international offices.

By the time she arrived at Quilter, Stephanie had already learned a critical lesson: industries change, but operational chaos does not. What changes is who is willing—and able—to stand at the center of it.

Being Non-Technical in a Technical Company

When Stephanie joined Quilter, she became the only non-technical hire on a deeply technical team. “I felt a bit intimidated by that,” she admits. Rather than retreat, she leaned into curiosity as a strategy.

Her philosophy is simple but deliberate: context matters. “I think it is really important to learn… be curious. Like, what does this mean?” she explains. When unfamiliar technical concepts surfaced—plotters, demos, customer workflows—she made note of them and asked questions directly. “I’m a questions girl. I’ll always be curious.”

Stephanie does not believe non-technical roles require mastering every technical detail. But she is firm that credibility depends on understanding how the business actually functions. “The more context you get, the more awareness you get… it helps you prioritize their work,” she says, describing how technical literacy enables better decision-making, scheduling, and support.

At Quilter, this curiosity translates into action. She plans to sit in on technical demos, observe customer reactions, and learn the rhythms of how Quilter’s product lands with engineers. “That just helps me learn the business better and gives me a better idea of how to navigate through it.”

This approach mirrors Quilter’s own philosophy: understanding systems deeply enough to make better decisions, without pretending complexity doesn’t exist.

The Work No One Sees

There’s a common misconception Stephanie is quick to challenge. “People assume the role is limited to scheduling meetings or ordering lunch,” she says. “In reality, my work is about building infrastructure from the ground up.” At Quilter, her role functions as a true executive partnership—focused on creating systems that enable scale, fostering a warm culture, and ensuring team members feel genuinely supported and empowered to thrive.

She estimates that only about 40% of her work resembles traditional executive assistant tasks. The rest is operations, problem-solving, and organizational design. “We’re a startup so we got to figure all of that out,” she explains—state accounts, insurance, payroll issues, office space, vendors, onboarding processes that didn’t previously exist.

“There’s fires going everywhere,” Stephanie says, describing the reality of early-stage startups. Insurance issues surface unexpectedly. Payroll questions demand immediate answers. Flights need to be booked overnight. Meetings must be restructured at a moment’s notice. Office brokers fall through. Systems that don’t yet exist still need to function as if they do.

It requires a particular temperament—decisive, adaptable, and relentlessly solutions-oriented. Stephanie likens the role to motorsport, where performance depends not just on the driver, but on everything happening around them. As she puts it, “An exec without a great executive business partner is like a race without a pit crew—capable of high performance but constantly slowed down by preventable obstacles.”

At Quilter, her job is to remove those obstacles before they ever register as friction. The work is rarely visible, but its absence would be immediately felt.

Becoming the Source of Truth

When Stephanie joined Quilter, there was no onboarding playbook. “It was really like, ‘You’re here… figure it out,’” she recalls. From day one, leadership directed questions to her. Within months, she became the company’s connective tissue.

“I would say I'm the source of truth for everything now,” she says. Even when she doesn’t have an immediate answer, she knows how to find it—and who needs to be connected. “If I don’t know it, I will find out the answer for you and I’ll pinpoint you in the right direction.”

This role is especially critical in a hardware-driven organization. Engineers, as Stephanie and Cody both note, are not always drawn to bureaucratic navigation or logistics. They need someone they trust—someone who can absorb friction without amplifying it. Stephanie does exactly that, often invisibly.

“Executive business partners are like musicians who make everything happen,” she reflects. “You don’t see the background, you don’t see what we’re doing, but we’ll always make it happen.”