Read the Full Series

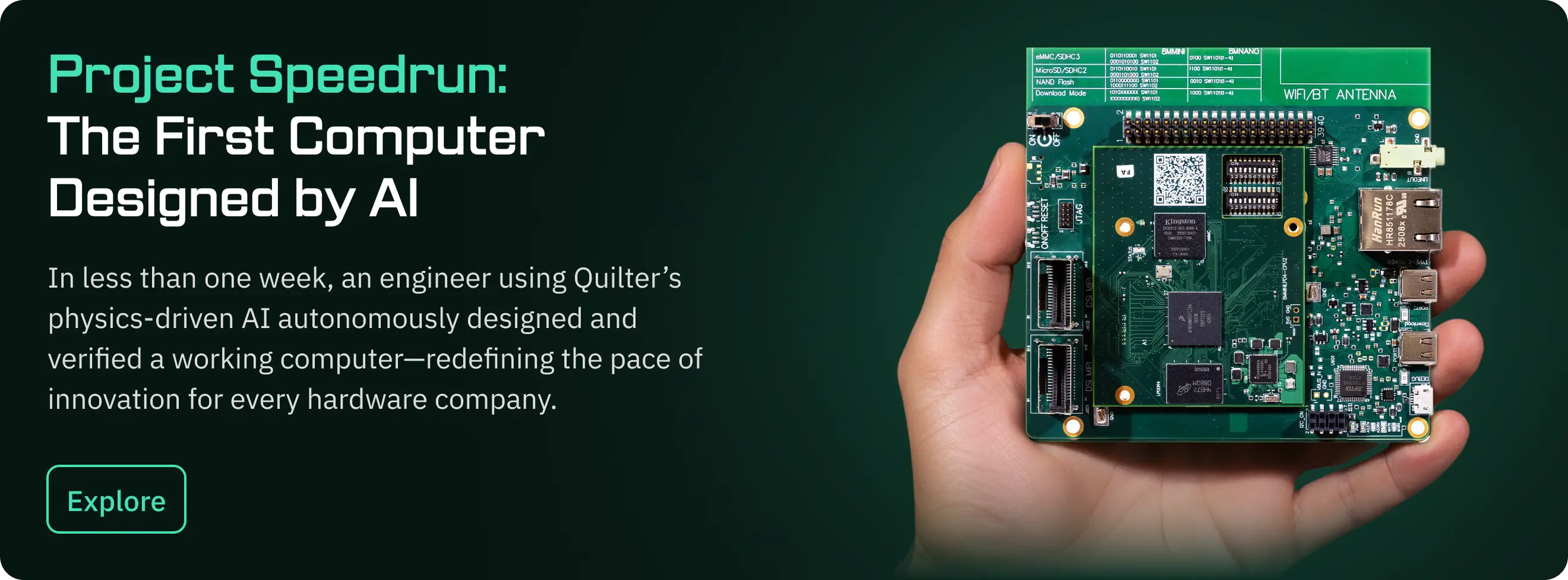

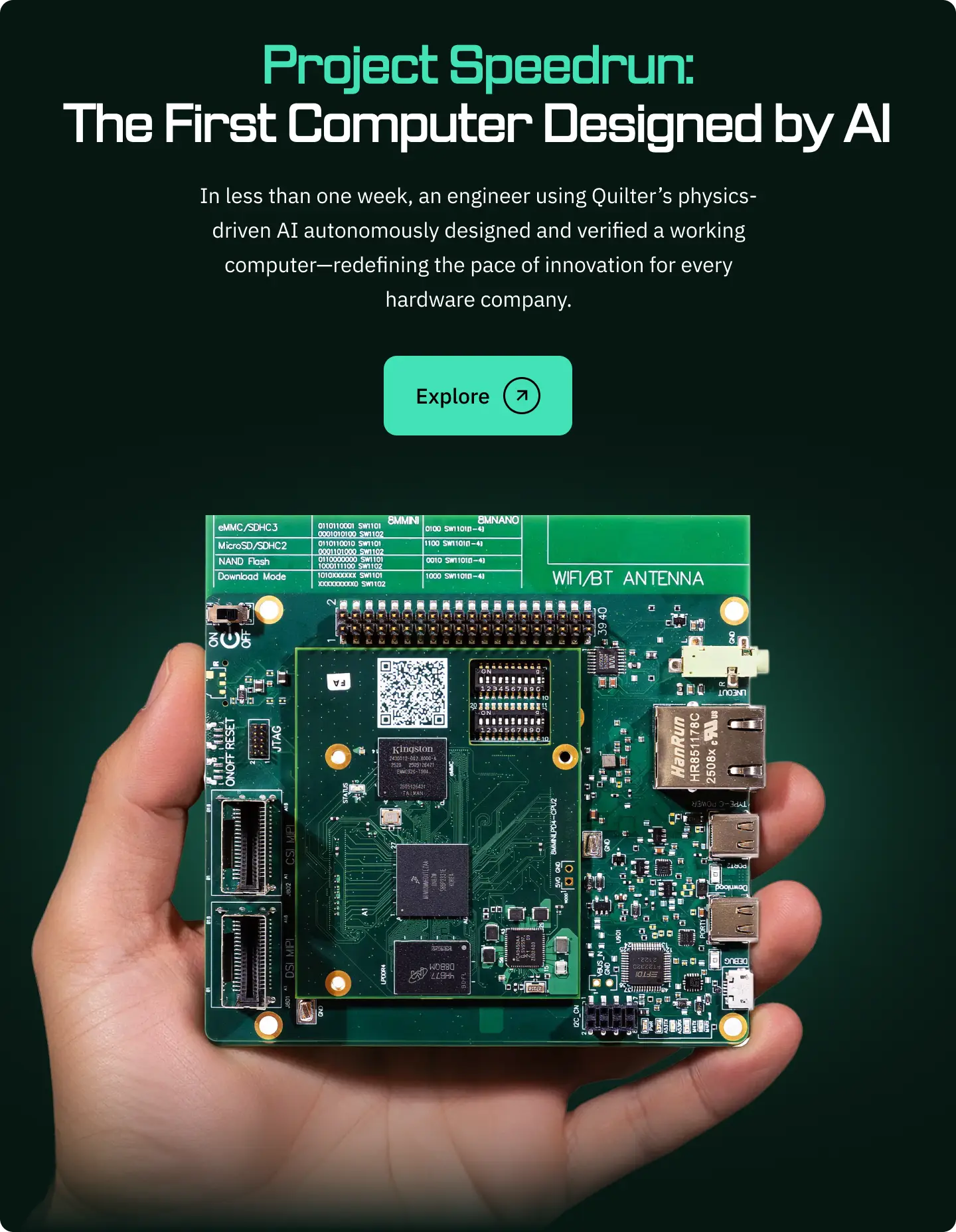

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

James Krejcarek speaks about making things with the reverence of a craftsman. In conversation with Cody Stetzel, he traces a line from woodworking and wind tunnels to printed circuit boards and poured copper. As Quilter’s VP of Sales, he treats sales as relationship-building and product as partnership — a collaboration with people who make. For James, engineering is not only about efficiency; it’s about enabling that human moment of surprise when someone sees something for the first time.

“Everything we do should be about building trust with our potential customer base. And no part of building trust is about over-promising.”

Origins

Originally from the Mid West, James learned early that making things well begins with a deep understanding of the tools used. “As you become good at making things, you really understand how to get the most out of the tools you use,” he said. He compares great engineers to carpenters who know “what grits of sandpaper, what tools you need on the lathe, [and] that you need your floor clean.” That sensitivity to craft would later shape how he leads teams both grounded in empathy for creators and in the belief that honest constraints are fertile ground for innovation.

“Being more honest about what we cannot do actually gives us a place where the person on the other side doesn’t have to say yes — but it gives them a much better ability to say, ‘Oh, okay… this is where I want to work.’”

Journeys in Engineering

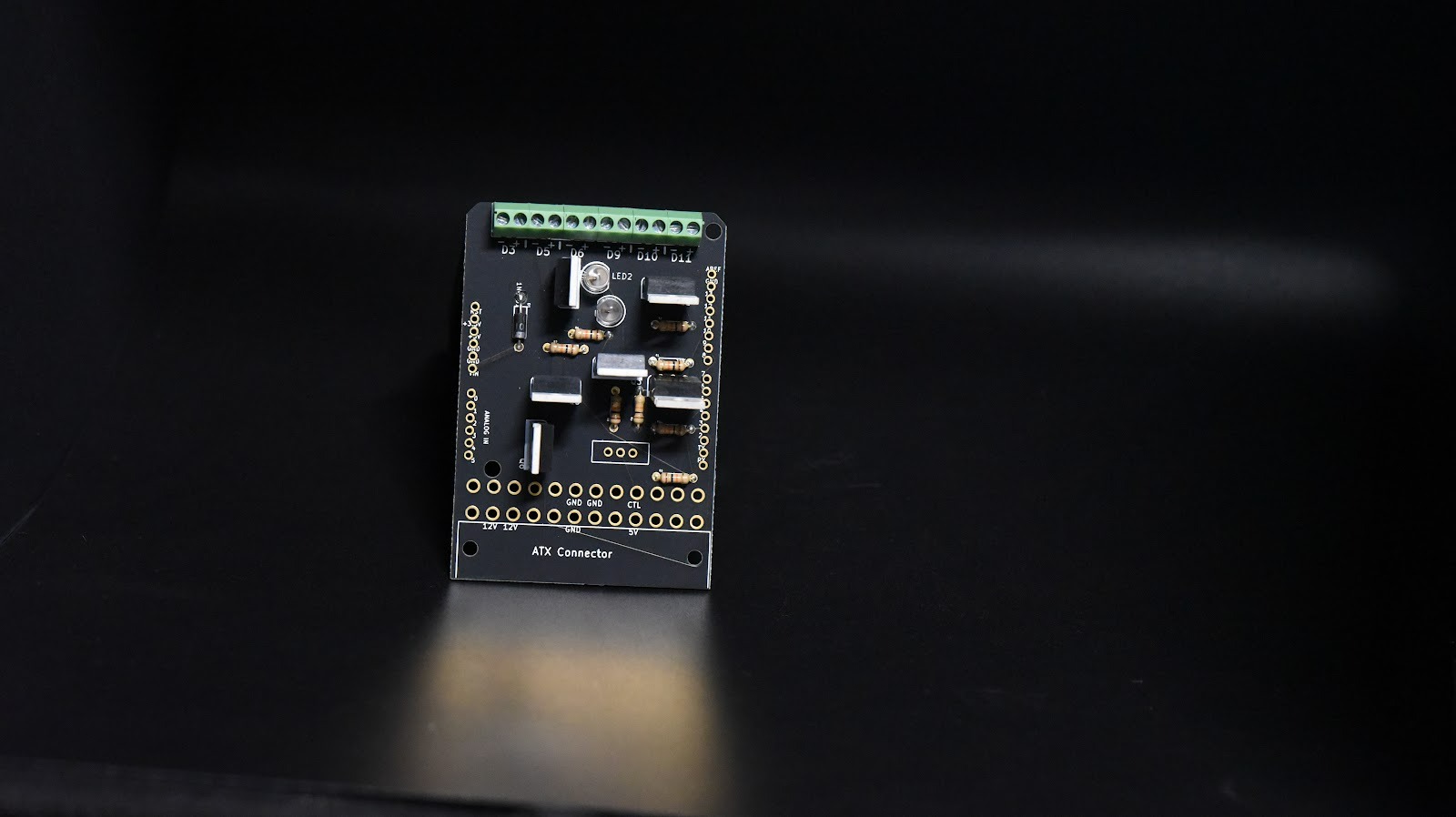

James views technology as an unbroken lineage of toolmaking. Quilter, he explains, is “making a tool and providing it to craftsmen. If we can help them get closer to their vision… taking an absolute blank slate and then putting in its place printed fiberglass and poured copper, that actually brings an idea to reality.”

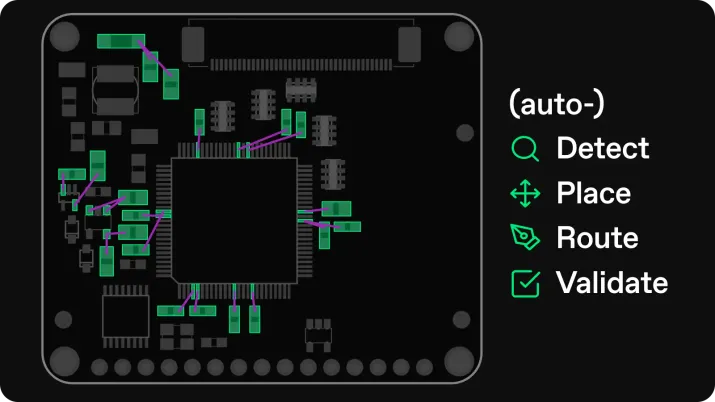

He delights in seeing that transformation firsthand: “We pulled up the board that was sent over… and you hear, kind of quietly, and it grows — ‘That’s neat. Doesn’t look like what a human would do, but boy, that’s neat.’” That small moment, he says, is a signal of something larger, something that engineers are returning to, experimenting with, and trusting again. “They’re coming back over and over again and checking in. That, to me, is an incredible indicator that we’re tapping into something more than just a curiosity.”

Why Quilter

James connects Quilter’s ambition to the Wright brothers recalculating lift and drag after realizing accepted data was wrong. “It was about a small group of smart, hardworking people getting to the heart of the problem and figuring it out,” he said.

For him, Quilter sits at a similar inflection point: “Maybe we’re at a moment where we now have the tooling and understanding to address it directly. The result will be surprise and delight on top of addressing the limitations everyone faces.”

He calls Quilter’s mission “an approach using the best of what we know with the best brains to come up with potentially more beautiful solutions.” It’s not about chasing hype — “This isn’t a large language model… this is using the best of what we know.” It’s about giving engineers better tools to turn vision into hardware, the true “moment of interface” where software meets the physical world.

Beyond the Workbench

Outside work, James’s curiosity takes tangible form in food, family, and the ocean. “My favorite meal growing up was fruit dumplings: boiled flour dumplings filled with strawberries or peaches. I don’t know how we got away with that for dinner, but it was amazing.”

Now, he’s a self-proclaimed egg enthusiast, “In some other life I’m probably a line cook at a Denny’s… I love my eggs over easy, nice and runny.” Weekends mean surfing and “fun road trips” with his family, from backyard badminton to hiking “eight miles down to the aquamarine waterfalls of Havasupai Falls.” These moments of movement and discovery mirror how he approaches innovation: step by step, with wonder intact.

A Line to Remember

“I like to look for margins where nobody’s looking. This is a problem that’s not a new problem, but people have kind of written it off in terms of value. To finally be able to come back and say, ‘I don’t know, we’re gonna go get that value’ — that’s like searching for treasure.”

Closing Note

What stands out about James Krejcarek is his belief that engineering’s magic lives in emotional honesty, in knowing your tools, admitting their limits, and still daring to seek beauty through them. His approach reminds us why Humans in the Loop exists: to show that the best technology begins with trust.